Treading a fine line

Report on the future of coatings

Quotes from The Superyacht Report – Refit Focus | issue 227 | Quarter 4 / 2025 | words by Conor Feasy

You might not want to sit and watch paint dry, but as the margin for error diminishes, you will definitely want to keep an eye on how the coatings market is developing in the refit sector ...

Paint has been one of the more predictable parts of the yachting economy. Given typical coating-system degradation and cyclical repainting schedules, the work arrives with a degree of regularity that yards and suppliers accept as part of the territory. It’s that very predictability that has long made paint a dependable contributor to refit and, client-induced headaches aside, it’s caused little future-facing concern thus far. But looking at the fleet’s inflation, tightening environmental regulations that reduce coating effectiveness, rising labour and raw material costs, the notion that there is no cause for concern within this segment of the market is becoming difficult to sustain.

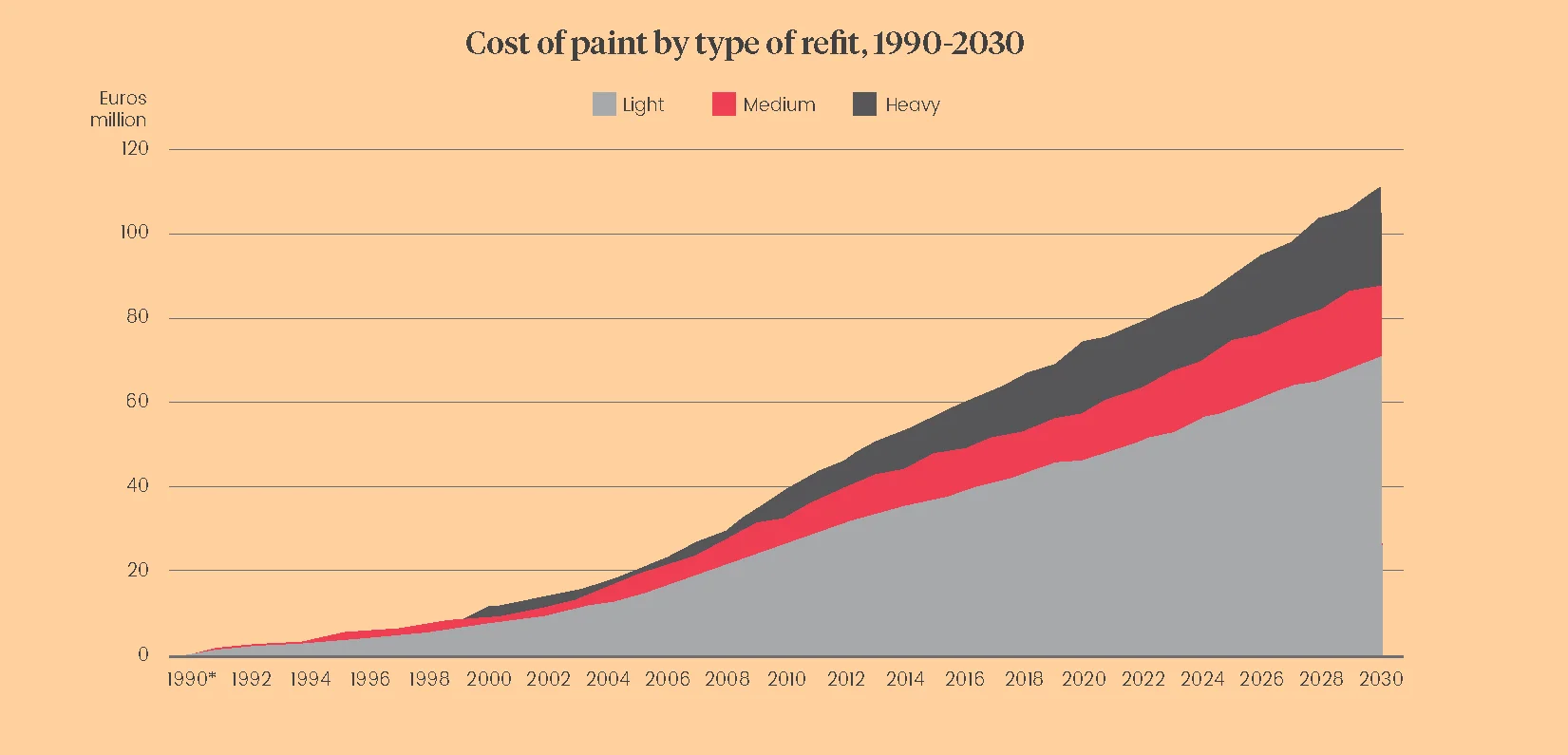

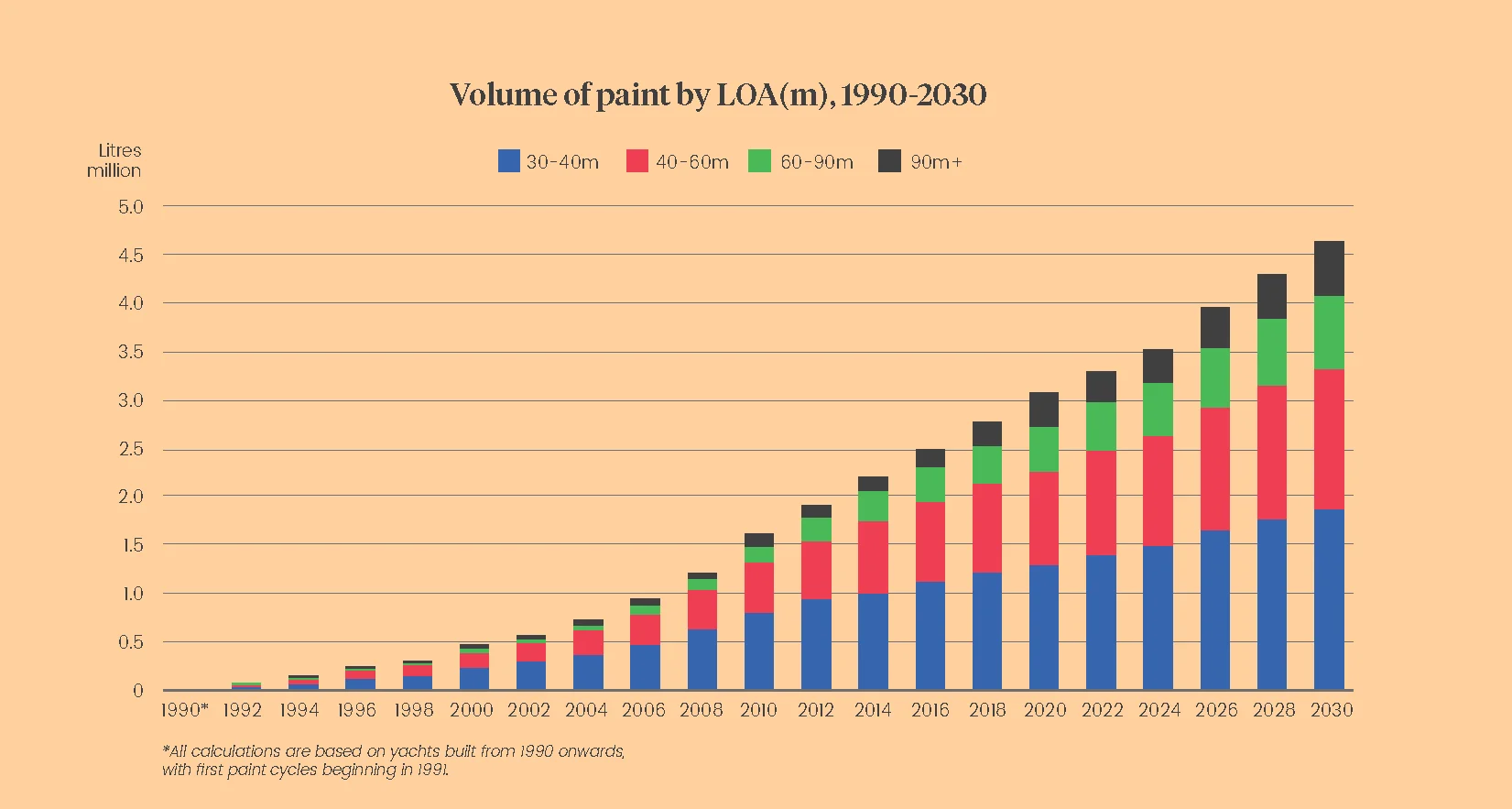

We’ve dissected data provided exclusively to The Superyacht Group by Wrede Consulting to map a forecast of where this stalwart corner of the superyacht sector will be in five years based on current data and market conditions. We’ve tracked the fleet from vessels above 30 metres launched in 1990 onwards to help contextualise the scale of the market with the fleet that is most actively in the repainting cycle. Paint volume is measured in litres of applied coating among three refit cycles – light (one year), medium (five years) and heavy (10 years). The reference to cost refers only to materials, not labour, which we have measured in hours per litre applied.

Source: The Superyacht Intelligence Team

There is more to the climbing data lines than meets the eye. At first glance, it might appear to be a standard chart of industry growth, but several things can be true simultaneously. The data indicate that stress points are accumulating pressure at a rate that could have serious detrimental effects on the entire refit market. This is not to say that a dramatic impact on the industry is unavoidably imminent, nor to say that shipyards are not already getting ahead of the curve. But this adaptation has to move in the right direction to avoid the former and achieve the latter.

In essence, the growth of the market, not just by the number of actual vessels in the fleet but the growth in the 60-metre-plus market, is leading to a bottleneck. A greater surface area entering repaint cycles requires more labour hours per litre applied. In absolute terms, this is a markedly different landscape from the one the industry faced even a decade ago. If we rewind to 2005, the market applied just under 860,000 litres of paint to refit projects each year. That’s around 1,200 Boeing 737s. But in 2015, that figure had risen to 2.4 million litres, an increase of 175 per cent over the decade (3,300 Boeing 737s). By 2025, it stands at 3.8 million litres, up 60 per cent in ten years. That’s a lot of jets and a total increase of 340 per cent over the past 30 years.

The next five years will add around another 900,000 litres, so there is no sudden break in trend. But by the end of this decade, the refit market is processing close to 5 million litres of paint annually, a level that fundamentally changes the labour, time and capacity required to deliver what remains ostensibly routine work in an already stressed market. Not to mention this data does not explicitly cater to the projected growth of the fleet by LOA. Although it may be a factor to some degree, it’s not necessarily changes to owner behaviour driving this growth, nor is it due to more frequent repainting across the fleet. The main driver is from the interaction between refit cycles and increasing fleet composition.

Source: The Superyacht Intelligence Team

The market by paint volume

Annual maintenance continues to absorb a large share of refit capacity. The pressure builds not from refit cycles but from how paint demand scales with yacht size. As vessels increase in length, the relationship between LOA and paint demand becomes nonlinear. Yachts above 60 metres account for around a quarter of total refit paint volume, but closer to 30 per cent of incremental growth over the forecast period. Their disproportionately larger exterior sur-face area results in more litres applied per metre, more hours per litre and more time spent on each project. Larger yachts also introduce greater technical sensitivity and scale. Increased surface temperatures on darker hulls, combined with modern fairing materials that are less forgiving, reduce tolerance and increase the likelihood of additional sanding and preparation cycles.

Set against that backdrop, the data shows a layered market driven by distinct refit cycles. Light refits, operating on a one-year cycle, form the foundation. In 2019, annual work accounted for just under 1.9 million litres of exterior paint. By 2025, this rises to 2.38 million litres, reflecting steady but persistent growth.

Heavier refits carry a different opera-tional weight. So while five-year repaint-ing accounted for around 440,000 litres in 2019, it rose to roughly 670,000 litres by 2025, and ten-year refits followed a similar trajectory. They increased from just under 580,000 litres to around 725,000 litres over the same period. And notably heavy refits are where the most disruption occurs – when paint outcomes are rejected on these projects, corrective work is rarely incremental and can involve re-scaffolding, re-wrapping and weeks of additional time alongside.

By 2030, the refit market is expected to support nearly 3 million litres of annual work, around 730,000 litres of medium refits and just over 1 million litres of ten-year refits, working alongside each other every year. And these operations rarely work in isolation. When paint schedules slip, the effects are felt across engineering, carpentry, rigging and outfitting, magnifying the impact of overlap between refit cycles. This layering of light, medium and heavy concurrently explains why head-line growth remains orderly even as operational pressures intensify. Light refits set the baseline, medium refits tighten sched-ules and heavy refits absorb disproportionate time, labour and capacity.

There are more refit projects in the ecosystem than ever before. And what is changing is how those projects behave once they enter the yard. As the fleet shifts upward, a growing share of refit paint volume and labour is attached to larger yachts.

The collision of size and cycle

Growth continues across all length segments of the fleet, but its con-sequences are uneven. An increasing share of refit paint volume is tied to yachts in the 60 to 90-metre and 90-metre plus categories. In 2019, vessels above 60 metres accounted for around 650,000 litres of exterior refit paint, equivalent to 23 per cent of total volume. By 2030, that figure rises to 1.32 million litres, representing around 30 per cent of the market.

This is where the scales could begin to tilt. There are more refit projects in the ecosystem than ever before. And what is changing is how those projects behave once they enter the yard. As the fleet shifts upward, a growing share of refit paint volume and labour is attached to larger yachts. These projects are longer, more complex and less forgiving of interruption. They sit in docks for longer, demand sustained access and absorb skilled labour for extended periods. When several coincide, they pull disproportionately on the same finite resources.

These are the reasons why pressure builds even as headline growth remains orderly. Project counts rise with litres of white, blue and (now a lot of) grey paint. But capacity tightens because a rising share of work occupies space for longer and resists compression. Schedules will lose elasticity, and the domino effect will compound for shipyards. Under these conditions, recovery options rapidly diminish. Early condition assessment, realistic and clear agreement on quality criteria, are seen by most refit operators as more effective than attempting to correct issues once work is underway.

As refits get larger and run for longer, more capital is tied up by default. By the end of the decade, the refit paint market will not just be busier but also less forgiving when projects slip ...

Four million more hours and counting

Labour is where the refit paint market’s long-established sense of predictability really begins to thin. Over the past two decades, demand has grown steadily, but the labour required to meet it has grown faster and with far less flexibility. In 2005, the coatings market absorbed around 3.35 million labour hours across all refit cycles. By 2019, that figure had risen to over 11 million hours. By 2025, total labour demand is projected to be nearly 15 million hours and by 2030, it is projected to reach around 19 million hours.

On the surface, paint volume and labour appear to rise in step. Over the period from 2019 to 2030, paint volume increases by just over 60 per cent, broadly in line with labour hours. Operationally, the two are not interchangeable. Labour is slower to expand and harder to substitute than material throughput. Modest increases matter when baseline capacity is already absorbed.

That pressure becomes clearer when labour is viewed through the lens of refit cycles. Annual work continues to account for the largest share, but heavy refits are absorbing a growing share of total hours. By 2025, ten-year refits alone require more than 3.3 million labour hours, rising to just under 5 million hours by 2030. These projects remain fewer in number, but their labour demands are sustained, intensive and challenging to reschedule. Length compounds the effect. In 2005, yachts above 60 metres accounted for just over half a million labour hours. By 2019, that figure had risen to 2.57 million hours. By 2030, it will exceed 5.3 million hours annually. That is roughly 605 years of continuous work by one person.

So what matters is concentration. A growing share of labour demand is tied to larger yachts, longer refits and narrower sequencing windows. By the end of the decade, the refit market will not simply be doing more work but also more labour-intensive work. Skilled labour, not paint, is where the refit market’s margin for error continues to narrow. And if labour is where the market tightens operationally, materials are where it becomes more exposed financially.

All this, and at what cost?

The refit paint market is not just getting more expensive because paint prices are rising. It is becoming more expensive because more paint is being used on larger yachts more often and simultaneously. Between 2019 and 2030, annual spending on exterior refit paint materials rises from €68.2 million to €110.3 million. Those figures assume no inflation and no price changes. Unit costs are held flat at 2025 levels throughout the forecast. The increase comes entirely from volume; more paint is moving through the system.

Another way to look at it is pace. On current pricing, the refit market will spend around 25 per cent more on paint materials over the next five years than it did over the previous five. That spending is not spread evenly either. As we’ve seen, heavier refits and larger yachts account for a growing share of material use. Ten-year repainting absorbs far more paint than it used to, and the fastest growth in material spend is in the 60 metre-plus fleet. It’s the same story: bigger yachts require larger quantities.

In practical terms, that means paint stops being a small, easily absorbed line item. Some commentators have even disclosed that they aren’t even making a (notable) profit from the work, but do it to maintain their reputation. Large systems also need to be purchased before the job is complete, often before labour demand peaks. When several long refits run concurrently, more paint is tied up for longer across fewer projects. If a project slips, the paint and capital remain committed.

It is important to be clear about what this does and does not show. These figures cover paint materials only. They exclude labour, access, scaffolding, containment and all other costs. They do not attempt to predict inflation or supply disruption. They simply show how much paint the refit market must purchase as the fleet grows and refit cycles overlap, based on today’s prices. Seen this way, materials are not the main constraint on delivery. Labour still determines whether projects can be completed on time, but materials shape the financial exposure underlying the work. As refits get larger and run for longer, more capital is tied up by default. By the end of the decade, the refit paint market will not just be busier but also less forgiving when projects slip.

That is the context in which adaptation stops being about capacity alone and becomes a question of planning. Rising volume should not be taken as a proxy for ease of delivery. The refit paint market is doing more work, on larger yachts, over longer cycles, with less room for recovery when outcomes fall short. The data shows no sudden break in trend, but it does point to a system where tolerance is steadily narrowing. Sure, paint remains a dependable contributor to refit, but its ability to absorb disruption is no longer what it once was.

Paint is where expectations, regulation and practical reality collide most visibly. The pressures aren’t due to a single change – skilled labour has become harder to secure and more expensive, particularly at the level required for large, high-profile yachts. At the same time, finish expectations have continued to rise, with darker hull colours and “near-new-build standards” now commonplace, even though refit conditions remain defined by existing substrates, access constraints and fixed schedules.

Environmental regulation has added another layer, with a variety of require-ments now shaping how paint projects are planned and executed. While generally accepted as manageable, their conse-quences become painfully apparent when outcomes are rejected: repeated sanding, extensive shrink-wrapping and weeks added to already complex refit timelines. Paint also rarely operates in isolation.

Taken together, these factors help explain why paint has become such a sensitive part of the refit equation. And how those pressures translate into day-to-day delivery is best understood through the captains of industry managing refits in practice.

The interviews describe a refit market that has become far less forgiving. Labour availability emerges as the primary con-straint and heads of industry consistently point to shortages of skilled painters, supervisors and inspectors as the most notable driver of cost and delay.

Of course, environmental regulation is widely accepted as a necessary part of the landscape, but it also carries practical consequences. Naturally, we look to technology, but it cannot compensate for poor preparation or unrealistic expectations.

Paint in the refit sector remains a technically mature and well-understood discipline but the margin for error is wafer-thin. More paint moving through established cycles means more labour tied up for longer and more projects whose outcomes are less tolerant of delay, which will have ripple effects across the market. That’s not to say the market can’t and won’t adapt, but it’s the canary in the coal mine indicating it should.

Quotes from Q&A with Stefan Coronel, General Manager HUISFIT by Royal Huisman:

WHERE DO YOU SEE THE BIGGEST PRESSURE ON PAINT REFIT COSTS TODAY – IS IT LABOUR, MATERIALS, REGULATION OR CLIENT EXPECTATION, OR SOMETHING ELSE? HOW HAS THAT BALANCE SHIFTED IN RECENT YEARS AND HOW DO YOU EXPECT IT TO CHANGE FURTHER?

Next to the basis of having the skilful craftsmen at work, two things are important to ascertain success. Firstly the agreement set of clear quality criteria and a well organised process of signing off by subject matter experts. To get to the desired result an accurately managed process of preparation, environmental control and obviously craftsmanship is key. It is important to realise that the biggest challenge on costs associated around the paint of refits is in the effects of any issue within the paint scope for other disciplines. Carpenters, engineers, riggers, outfitters, the progress of all the work may suffer serious effects when issues arise in the paint.

HOW ARE NEW ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATIONS AND SUSTAINABILITY GOALS CHANGING THE WAY PAINT PROJECTS ARE PLANNED, COSTED AND DELIVERED?

It sometimes takes adaptation to deal with new regulations or changing products due to the development of more sustainable materials, we believe this to be manageable and not a hurdle for the industry.

WHAT ROLE WILL TECHNOLOGY PLAY IN IMPROVING EFFICIENCY? ARE WE ALREADY SEEING A MEASURABLE IMPACT IN REAL PROJECT OUTCOMES?

Technology will often have a purpose in increasing efficiency. For example, advanced climate control and extraction systems help create optimal working conditions, ensuring that all disciplines can carry out their tasks without disruption. These technologies contribute to a comfortable, safe, and efficient environment, allowing work processes to run smoothly and productivity to remain consistently high.

LOOKING AHEAD, WHAT DO YOU SEE AS THE NEXT MAJOR CHALLENGE OR TURNING POINT FOR PAINT AND FOR THE WIDER REFIT MARKET? WHAT CAN BE DONE, OR IS ALREADY BEING DONE, TO ADDRESS IT?

I believe that traditional yacht paints are more or less fully developed, and we should start looking for new alternatives. A good example of this is the base coat/clear coat system. These high-solid products still offer plenty of room for innovation and have the added advantage of providing more easily repairable top layers in case of damage. For interiors, I would mainly consider water-based products, which have been widely used in residential construction for many years, but in which the yacht-building industry is still lagging behind.

you might like this too