There is an inescapable cyclicity to life. And in yachting, this is where passion meets purpose...

Quotes from article by The Superyacht Report – Refit Focus | issue 227 | Quarter 4 / 2025 | words: Conor Feasy, photos: Cory Silken, Mike Tesselaar, Priska van der Meulen, unknown.

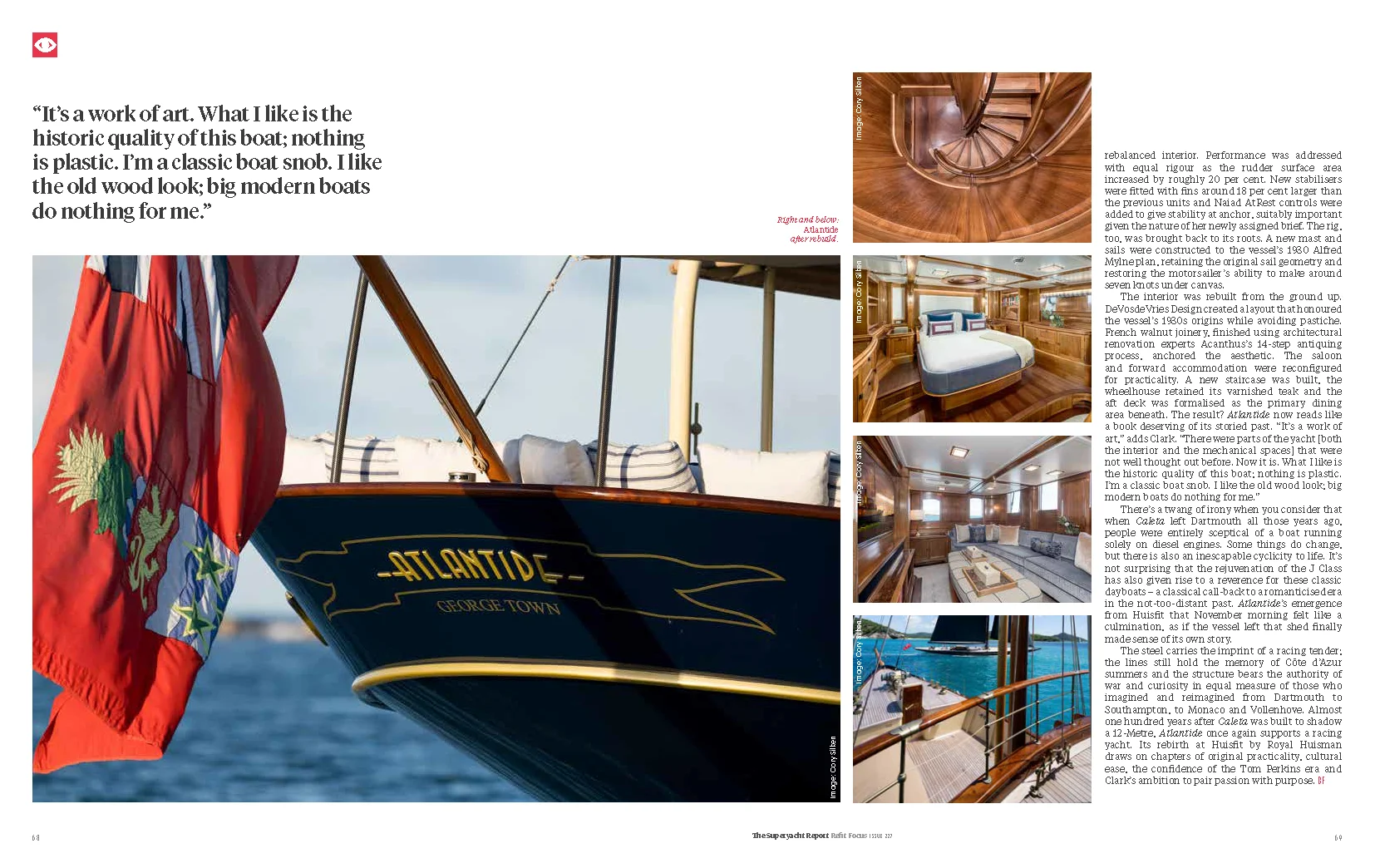

When Atlantide emerged from Royal Huisman’s Huisfit facility on a crisp November morning in 2023 you might have questioned your own perception. The Côte d’Azur icon appeared out of the autumnal mist as a simultaneous embodiment of an enduring present and a storied past. Approaching a century afloat, having supported championship sailors, featured on the silver screen, graced the golden era of Mediterranean yachting and rescued troops from the beaches of Dunkirk, Atlantide felt less like a restored yacht and more like a vessel reborn.

What began as a standard refit quickly became a complete rebuild under the stewardship of seasoned yachtsman and Silicon Valley trailblazer Jim Clark. His fleet includes some of the most ambitious sailing yachts of the past three decades: Hyperion, Athena, Hanuman and Comanche. The latter set the 24-hour monohull distance record in 2015 with a run of 618.01 nautical miles, then broke the monohull transatlantic record the following year, completing the crossing in five days, 14 hours, 21 minutes and 25 seconds.

When Atlantide entered the market, Clark saw potential for a classic motorsailer to complement his J Class. Rather than wait for a yard slot, he sent the vessel to the Netherlands immediately. Once opened, the project revealed far more than anyone expected, ultimately requiring the replacement of almost 40 per cent of the hull, deck, and frames. It was a seismic undertaking. To understand why Atlantide resonated so strongly with Clark and why the yard approached the project with such care, we must return to the beginning.

Atlantide’s story begins in 1930, although under a different name and in a different era. Originally launched as Caleta at Philip & Sons in Dartmouth, the craft emerged from a shipyard famed for dependable naval and commercial builds, so it was an appropriate birthplace for a commission that valued utility above display. The order came from Sir William Burton, a prominent figure on the British yacht-racing circuit in the early twentieth century, having helmed Sir Thomas Lipton’s America’s Cup challenger J Class Shamrock IV in 1920. Burton required a no-nonsense, sturdy, seaworthy vessel to operate as a support vessel for his 12-Metre races – one that was consistent enough to form the infrastructure behind competitive sailing, knowing firsthand the demands of a serious campaign. A 12-Metre does not operate in isolation, of course.

The design was penned by Alfred Mylne, who had established himself as one of Britain’s most exacting naval architects in the interwar years with a portfolio that stretched from racing yachts to auxiliary craft. His work balanced a timeless class with pragmatism, favouring clean lines, structural integrity and efficiency over complete luxury, principles Caleta reflected. The 37-metre motorsailer that took shape in the south of England had a slim steel hull and a functional rig that allowed the vessel to make around seven knots under sail when needed. The accommodation was restrained too, focused on operations. That clarity of purpose would echo through the decades, long after the name changed and long after the yacht found itself in far more dramatic circumstances.

A decade on from its launch, Caleta’s transition from racing support vessel to wartime asset came with little ceremony. Like many private craft of the period, the yacht was requisitioned by the Royal Navy at the outbreak of the Second World War. In May 1940, the Admiralty issued an urgent call for small vessels to join the evacuation of Allied troops from northern France – Caleta was among those that answered, and on 31 May, the vessel set out for Dunkirk in company with two other craft, Glala and Amulree.

Caleta during the Second World War. Nowadays this laurelled, historic Little Ship of Dunkirk is renamed Atlantide.

Crossing the channel was fraught with smoky horizons, aircraft whirling overhead amid the low percussion of artillery drumming ever closer, but Caleta and its crew continued operating off the beaches for the better part of a week. The defining episode occurred mid-operation, when the crew encountered a damaged landing craft still carrying 35 British troops. With the beaches under fire and evacuation routes narrowing by the hour, the yacht took the men aboard and attempted to tow the vessel back to England. But the state of the sea, strain of the tow and the sheer volume of traffic conspired against the effort to save the landing craft. The tow repeatedly failed; the crew of Caleta attempted to salvage whatever they could from the battle as the line kept breaking. But as air attacks persisted, so too did the resolve of those on board until all aboard, and the damaged landing craft, reached the shores of old Blighty. It was a role in one of the most extraordinary yet most poignant escapes of British history and an act that earned Caleta the right to fly the St George’s Cross, a distinction recovered for vessels of Operation Dynamo.

Caleta returned to civilian ownership in 1946, when the vessel was sold to a Greek yachtsman, who renamed it Ariane; the transfer marking a major two-year rebuild at Vosper Thornycroft in Southampton. The work ultimately modernised the vessel by overhauling the steelwork and reconfiguring the accommodation, resetting the yacht for a new chapter after the strain of wartime service. By the early 1950s, Ariane had settled into a long Mediterranean life. For nearly 50 years, the vessel cruised between the South of France and the eastern Med, becoming a familiar presence in Cannes, Antibes and Rhodes during what is fondly referred to as the golden era of yachting. And while it might not have been the headline act, it was easily recognised by its proportions and white hull, which became a visual signature throughout this period.

In 1960, however, the yacht was renamed Corisande, only to appear on the screen two years later in the 1962 adaptation of Tender is the Night, featuring in sequences filmed along the Riviera. It was a brief role, but it places the yacht in the wider cultural memory of the era and offers a rare, fixed point in an otherwise lightly documented chapter of its life – there are no small roles, only small yachts, after all.

Jennifer Jones onboard Corisande, formally Caleta, on the French Riviera, in the 1962 film, Tender is the Night.

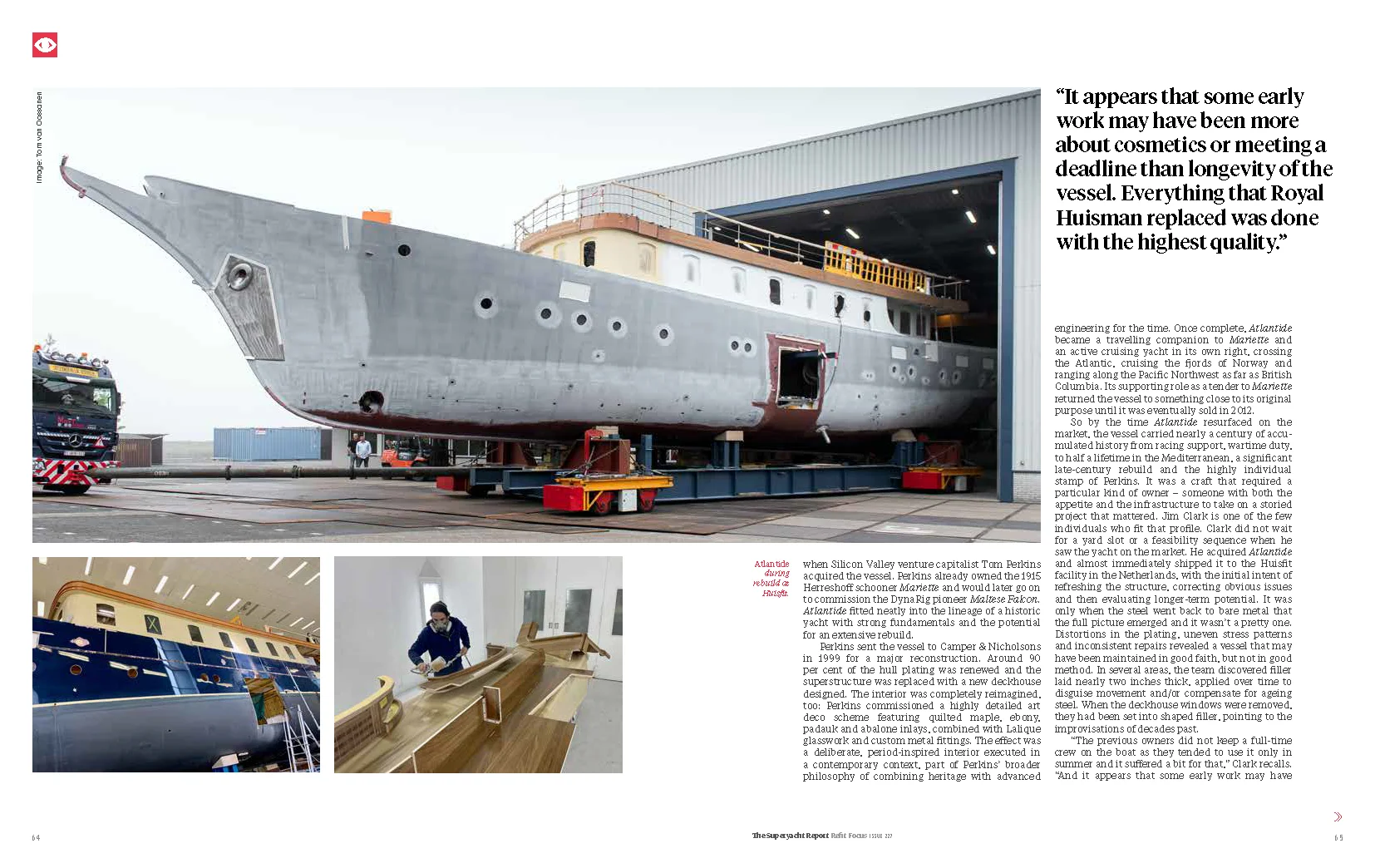

The next noteworthy change came in the late 1980s when Venetian aristocrat Count Nicolo dalle Rose acquired the vessel. He restored the white hull once more and named it Atlantide, which the yacht has carried ever since. Under his ownership, the vessel was based in Monaco. Then nearly 70 years old, Atlantide entered a new phase in 1998 when Silicon Valley venture capitalist Tom Perkins acquired the vessel. Perkins already owned the 1915 Herreshoff schooner Mariette and would later go on to commission the DynaRig pioneer Maltese Falcon. Atlantide fitted neatly into the lineage of a historic yacht with strong fundamentals and the potential for an extensive rebuild.

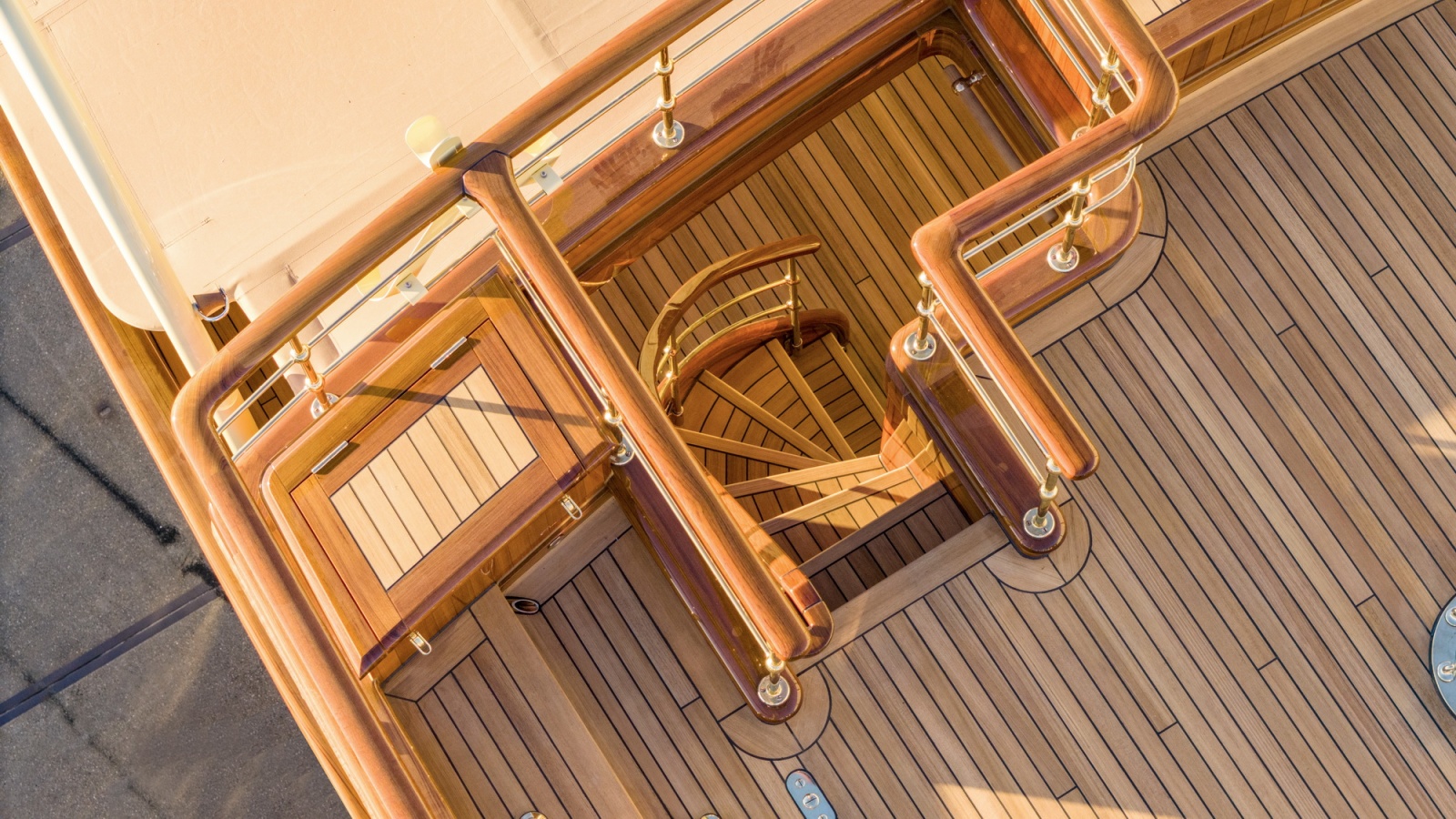

Perkins sent the vessel to Camper & Nicholsons in 1999 for a major reconstruction. Around 90 per cent of the hull plating was renewed and the superstructure was replaced with a new deckhouse designed. The interior was completely reimagined, too: Perkins commissioned a highly detailed art deco scheme featuring quilted maple, ebony, padauk and abalone inlays, combined with Lalique glasswork and custom metal fittings. The effect was a deliberate, period-inspired interior executed in a contemporary context, part of Perkins’ broader philosophy of combining heritage with advanced engineering for the time.

Once complete, Atlantide became a travelling companion to Mariette and an active cruising yacht in its own right, crossing the Atlantic, cruising the _ords of Norway and ranging along the Pacific Northwest as far as British Columbia. Its supporting role as a tender to Mariette returned the vessel to something close to its original purpose until it was eventually sold in 2012.

So by the time Atlantide resurfaced on the market, the vessel carried nearly a century of accumulated history from racing support, wartime duty, to half a lifetime in the Mediterranean, a significant late-century rebuild and the highly individual stamp of Perkins. It was a craft that required a particular kind of owner – someone with both the appetite and the infrastructure to take on a storied project that mattered. Jim Clark is one of the few individuals who fit that profile. Clark did not wait for a yard slot or a feasibility sequence when he saw the yacht on the market.

He acquired Atlantide and almost immediately shipped it to the Huisfit facility in the Netherlands, with the initial intent of refreshing the structure, correcting obvious issues and then evaluating longer-term potential. It was only when the steel went back to bare metal that the full picture emerged and it wasn’t a pretty one.

Distortions in the plating, uneven stress patterns and inconsistent repairs revealed a vessel that may have been maintained in good faith, but not in good method. In several areas, the team discovered filler laid nearly two inches thick, applied over time to disguise movement and/or compensate for ageing steel. When the deckhouse windows were removed, they had been set into shaped filler, pointing to the improvisations of decades past.

What followed was one of the most substantial restorations the yard had taken on. Close to 40 per cent of the hull, deck and internal framing was recreated entirely with the precision expected of a new build.

Atlantide during the rebuild at HUISFIT by Royal Huisman

The St George’s Cross, a distinction recovered for vessels of Operation Dynamo.

Jim and Kristy Clark felt that she would make a charming accompaniment to their J Class racing yacht.

Read on about the rebuild of Atlantide: The rebirth of a legend

you might like this too

.jpg?resolution=1600x900&quality=95)

.jpg?resolution=1600x900&quality=95)

.jpg?resolution=1600x900&quality=95)

.jpg?resolution=1600x900&quality=95)

.jpg?resolution=1600x900&quality=95)